Mission: Essen

Date: 1/2nd June 1942 (Monday/Tuesday)

Unit: No. 10 Squadron

Type: Halifax II

Serial: L9623

Code: ZA-O

Base: R.A.F. Leeming, Yorkshire

Location: North Sea - Dutch coast

Pilot: P/O. Edward Ronald Senior 107313 R.A.F.V.R. Survived (1)

Fl/Eng: Sgt. Hessel R.A.F.V.R. Survived - injured

Nav: Sgt. Griffiths R.A.F.V.R. Survived - injured

W/Op/Air/Gnr: Sgt. Hampton R.A.F.V.R. Survived

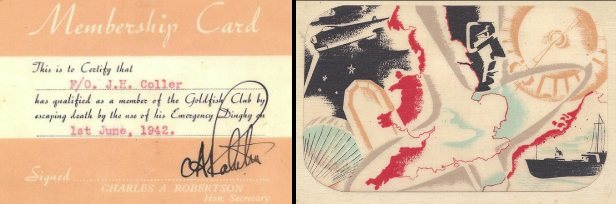

Air/Gnr: Sgt. John Coller R.A.F.V.R. Survived

Air/Gnr: Sgt. John Whitfield 954271 R.A.F.V.R. Age 25. Killed

REASON FOR LOSS:

Took off from R.A.F. Leeming, Yorkshire at 23.56 hrs to take part in the second large 1000 bomber raid on Essen.

Despite reasonable weather the crews experienced difficulty in finding the target as the ground was covered by a layer of cloud. The resulting bombing was scattered the city reported that only 15 people had been killed and 91 injured.

The raid took it's toll on the bomber force with 35 aircraft lost. A total of 140 aircrew were killed and 47 made p.o.w.'s.

No claim has been identified as to the night fighter responsible for Halifax L9623, but as clearly shown in the eye witness account of this loss they were indeed attacked by a night fighter.

One other aircraft lost from 10 squadron on this operation. Halifax W1098 flown by P/O. David Joyce, killed with 5 other crew members. One member surviving as a p.o.w.

(1) Tragically P/O. Edward Senior was later killed just a few weeks later when the Halifax he was flying BB201, was lost without trace on an operation to Emden. All crew were also killed.

Sgt John Coller describes the events of this loss:

"We crossed the Dutch coast at 12,000 feet homeward bound after dropping our bombs on Germany’s industrial centre in the Ruhr Valley where a large percentage of the enemy’s munitions were being made at the time. It was a dark night, no moon, but this was a normal condition for a homeward-bound aircraft after a bombing raid. We were home free, de-briefing, ham and eggs breakfast, a short sleep and then off again tomorrow night.

Suddenly the sickening thud of cannon shells piercing the soft skin of the aircraft’s right wing, which started a fire in the fuel tank, caught our attention. The rear gunner reported his guns jammed and we started to go down into the darkness below. Engines 2, 3 and 4 quit and No.1 was a runaway, pulling us over into a spiral vertical dive towards the sea below. The centrifugal forces pressed my body against the fuselage wall so that I could not move. I caught a brief glimpse of the attacking aircraft. a twin engined Messerschmitt, as it passed overhead, a victor in this brief skirmish. We had to get to the sea as soon as possible since we were on fire in the right wing which could separate due to the intense heat; but on the other hand the question going through my mind was whether we could survive the impact.

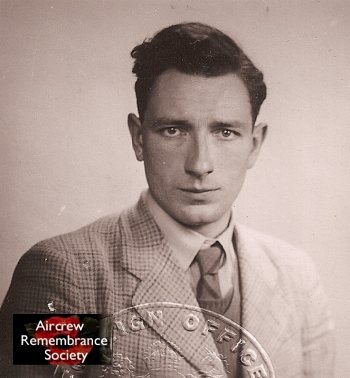

Sgt. John Coller (Courtesy Virginia McCammom and Jualene Tapp)

We had a relatively green, very young captain who had flown Condor aircraft in South America briefly; and an English trainee pilot who had been a London bus driver just 90 days before, with no operational experience. He was “a 90 day wonder” as we used to call the poorly trained English bomber pilots who were being shot down faster than they could be put into service at the time. With nothing to judge our altitude by but an altimeter, with zero cockpit lighting due to cannon damage, these two men brought that aircraft out of a terminal dive and somehow flared out for a semblance of a crash landing on the water which turned out to be survivable by most of the crew. The two men in the forward compartment suffered broken legs, and the rear gunner was killed exiting the turret astern as the plane broke in half upon heavy impact with the sea.

As I moved forward through the rising water in the cockpit, I collided with the injured navigator and bombardier who floated up from their stations in the rush of water entering the nose of the plane from below. We got them out on the left wing, fumbling in the near darkness as the plane was sinking and found that enemy fire had immobilised the dinghy release mechanism. Desperate, we dug the dinghy out of the wing with our boots as the wing submerged.

The sea was choppy as we tried to pump up the dinghy by hand in the darkness, (since the compressed air bottle did not work), trying to stay afloat as we worked. Eventually we were able to climb into our soaked refuge and sort out the bodies for minimal comfort as we bobbed about, thankful that we were still alive if a bit banged up.

Realising that the rear gunner was missing, I clambered aboard the sinking plane to try to locate and possibly save him. But the plane was sinking too fast and as I exited the hatch, I noticed a flash light on a clip near the door which I grabbed as I returned to the dinghy and rejoined my crew. That last action may well have made the difference between survival and a totally different turn of events.

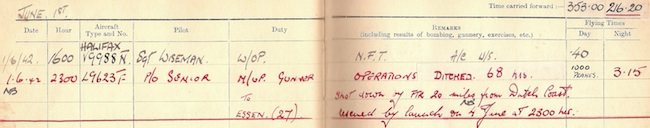

Log book entry for Sgt. John Coller (Courtesy Virginia McCammom and Jualene Tapp)

It was still pretty dark by the time we sorted ourselves out in the dinghy, probably 1:30 A.M. and we could hear our planes overhead as they returned to their bases in England.

A thought occurred to me as a radio operator. “What if they could see a signal from us, get a position fix, and then report it during debriefing when they got home?” I repeatedly sent a signal with the flashlight I had found upon leaving the plane. S----O----S,

S----O----S, as I pointed the beam approximately in the direction of the noise overhead as each plane passed by at about 10,000 feet altitude. Chances were small that anyone would see the signal that far up, and, for that matter, recognise it as a distress call, and have the presence of mind to record a fix of our position and report it.

We set about trying to make the injured comfortable. There were six of us in that small dinghy, and we did our best to make the fellows with the broken legs comfortable by grabbing pieces of drift wood to use as a splints and placing their legs up on the side of the dinghy so that they would not be crushed as the chop threw us around. Our navigator estimated we were 10 miles off the enemy coast and a long way from home. The wind was brisk and we had no idea what currents were doing to our little dinghy, possibly causing us to drift towards the nearby, occupied Dutch coast.

Sgt. John Coller (Courtesy Virginia McCammom and Jualene Tapp)

Dawn came slowly and we broke out the meagre rations which had been stored in the dinghy, concentrated chocolate bars and a small amount of water. After a while we heard an aircraft approaching from the West at about 2,000 feet. It was a Lockheed Hudson a twin-engine plane, which circled and dropped some supplies, most of which were lost. Almost immediately two German Messerschmitt 109’s came in from the East and started firing at the un-armed rescue plane, which took off for home followed by the enemy.

Later as the fighter planes returned, they flew low overhead firing their cannon clearly telling us that they could have easily sunk our dinghy with one burst of fire. We never did hear what happened to the rescue plane, because British intelligence would release nothing during the War.

Believe it or not, the very next day another similar friendly aircraft arrived overhead and circled until two Focke-Wolfe 190’s flew in and chased the would be rescuers off. The strangest thing happened the evening of the second day, when a German E-Boat approached and circled us at about ¼ mile away but never signalled or made any attempt at rescue. Then he was gone. We learned later that the London press had banner headlines, “Germans use downed crew as bait”.

(Courtesy Virginia McCammom and Jualene Tapp)

We had camouflaged our dinghy with battle dress, etc., after asking the injured if they could hold out for a while longer. Nobody really wanted to end up in a P.O.W. camp at this stage, even those poor guys with their injuries, who really needed medical attention! At one point, in a rare moment of humor, we heard the unmistakable bark of a dog, which made some of us wonder whether we were losing it already. We scanned the sea around us and suddenly a seal showed its head and barked again as though to say, “What in hell are you doing out here?”

During another incident, an argument arose when a ‘Walrus’ flying boat, search aircraft flew overhead at 2,500 feet, but was already well past us when we saw it. “Set off the flare” was the cry from most of the crew! I would not budge since it was our last flare on board, and I was determined to save it for when it really counted. You may wonder why the skipper did not give me a hard time. You see I had already completed one tour of 25 missions and I was already a “veteran”, flying as a :Safety Radio Operator”, with a trainee on the set. The rest of the crew had little operational time logged.

On the third day, a change of plan, a Bristol Beaufighter arrived very low, below radar, and circled once. The pilot waved and then was gone. We were encouraged that they were not going to leave us to the Germans without some effort at rescue, dangerous as that certainly would be. More importantly, they still knew where we were. Our hopes rose. That night the most incredible thing happened. There was this loud commotion to the South. Many planes circling. We were sure they must be ours, but it appeared that they had mistaken our position. After a few choice words we got ready for another night on the water. Little did we guess that it was all part of a diversionary plan to throw the Germans off .

I was peering around a little later when I saw a wonderful sight!, A small boat, an HSL, about a mile and a half away to the West, was creeping through the haze silently searching. “There they are,” I yelled. What a moment of relief that was! I immediately set off our last signal device (which I had held onto against many protests from the crew for just such a moment). The boat was alongside in minutes and with some help from the brave rescue crew we were aboard and headed for home at top speed. Wrapped in fresh blankets we all fell asleep.

I cannot hope to do justice to the brave men who risked their lives to save us, and to the remarkable tenacity and courage the Senior Officers showed in never abandoning us despite the enormous costs and the risks involved in this amazing rescue against all odds.

My dear parents, who of course had. been informed that we were missing in action for three days, were also quite relieved to get my phone call from the hospital upon our arrival back in England.

Those of us who were physically able were back on base flying again over hostile territory within 3 weeks, only to be brought down again by a fighter over occupied France as the war went on.

But, that’s another story." (See "HERE")

John Coller

We would like any relatives to contact us regarding this loss for any further information they maybe able to supply and for placing them in contact with others

Burial details: Sgt. John Whitfield. Commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial Panel 96. Son of George Lumley Whitfield and Mary Jane Whitfield, of Stanley, Co. Durham. At a later date: P/O. Edward Ronald Senior. Commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial Panel 71 No further details as yet. Information supplied by the relatives of Sgt. John Coller, Virginia McCammom and Jualene Tapp Acknowledgments: With thanks to the following: Bill Chorley - "Bomber Command Losses Vol 3", Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt "Bomber Command War Diaries", the superb work of the C.W.G.C.